Speight’s Wagner Memories: 2000 Half-RING

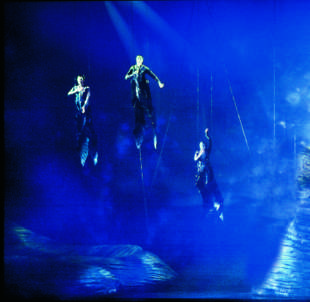

Lisa Saffer (Woglinde), Mary Philips (Wellgunde), and Laura Tucker (Wellgunde) in Das Rheingold, 2000

© Gary Smith

Financially, this very expensive project was carefully planned. We knew that it would sink the company if the money were not raised beforehand, and we did in fact raise more than $9 million before rehearsals began. We also sold out all three cycles one year to the day before the first performance.

The planning was more than complicated and completely unlike the kind of helter-skelter situation in which we had put together the previous Ring. In that one, only Rochaix’s amazing sense of personal organization and genius kept us on track. For this one, we had a two-week technical rehearsal in June of 1999, when we determined that all the set pieces worked. In August 2000, there were ten performances of Das Rheingold and Die Walküre (three of the former and seven of the latter), and finally the next summer three cycles of the complete Ring.

Wadsworth would tell anyone that he hates preparing schedules more than any other task as a director, but he did it: he prepared a detailed schedule for the rehearsal periods in both 2000 and 2001, more times than once, taking into consideration the changes that occur in singers’ availability, sicknesses, and technical requirements. His work, the labor of the Ring production manager Vinnie Feraudo, the technical director Robert Schaub, and the stage manager Clare Burovac, allowed us to bring the most complicated venture in the history of Seattle Opera into a safe harbor.

The technical viewing of Tom Lynch’s sets, in 1999, was basically a joy. The big news was the use of a digitizer to create the final sets. With this computer wand attachment, a new piece of equipment for Seattle Opera, the artisans were able to translate the dimensions of the organic-shaped models into the dimensions needed for the full sized sets. The final results looked as natural as real forests.

Wadsworth set out to create a real theater piece in Das Rheingold. The second and fourth scenes of the opera take place on a ridged terrain, inspired by Hurricane Ridge on the Olympic peninsula, west of Seattle. The first problem came when Gabor Andrasy, our Fafner, had to drop out for health reasons (he was in good health the next summer). He was replaced by a fine Dutch bass, Harry Peeters, who was covering another role.

In the Rochaix-Israel Ring, the most difficult scene, or at least the most rehearsed scene, was the opening of Walküre, Act III, with the flying horses. In this Ring, it was the even longer first scene of Das Rheingold. The Rhine Daughters actually swim in the air. Seen behind a scrim that suggests water, they perform aerial acrobatics up to 26 feet off the stage. They flip in the air as they sing; they constantly make swimming motions; their costumes are the classic stuff of mermaids. When I first saw them perform, I thought the Cirque de Soleil had no one better, and I still think that. To get to their degree of perfection, the three young women had come out to Seattle the previous winter and had begun to work off of pipes three or four feet off the floor. Long before that, our chief carpenter, Tim Buck, had worked out a flying costume that would be comfortable for them to wear. We had started work on this in 1996 or 1997, putting a local singer in a variety of harnesses to determine what was comfortable over a twenty-minute period, and what would be best for singing. After rehearsals began, Stanley Garner, Wadsworth’s associate director, worked unceasingly with the three singers. They planned the choreography and did it on the ground and then just off the ground; gradually, they moved higher, and finally they came to the Opera House and actually performed at the requisite height. The amount of work, the number of hours, the dedication involved was staggering. Lisa Saffer, Mary Phillips, and Laura Tucker, together with the crew members who “ran” them or who moved them (one man handles up and down movement, another the lateral motion), deserved the wild cheers the audience gave them.

The whole rehearsal period—from June 12 until early August—ran smoothly, with everyone from Jane Eaglen, our Brünnhilde, to Thomas Studebaker, the Froh, present, accounted for, and working hard on creating live, breathing, involved characters.

Nothing untoward had happened until the orchestra rehearsal prior to the dress. The third scene of Das Rheingold, the Nibelheim, is a black platform, elevated off the stage about ten or twelve feet. It is covered by black plush as is the area behind it. Veins of gold are seen through the black, and in performance the singers seem to be floating in mid-air in a mine with gold all around them. The illumination comes from lights on either side of the stage. As the major part of the scene involves only three people at most, each person has a light and must not get in front of any other person’s light. That way the illusion of floating can be maintained, and each character can be well lit. This technique is called cross lighting. Wadsworth had asked Peter Kazaras, the Loge, to move a bit more to his left in one scene. The platform had little warning lights at its edge. Kazaras, singing, moved to his left, ignored the lights and—went off the platform. He fell with a sickening thud. Wadsworth and I almost flew up on the stage as Jordan stopped the orchestra. Kazaras had been in college with Wadsworth, and he has been a close friend of mine for almost twenty years, so we were personally and professionally terrified. Kazaras was already on his feet, saying that he was fine. The odd thing was that this was not a “shock” reaction. He really was fine. Maybe he broke his fall by touching the platform as he went down; maybe his guardian angel was protecting him. But in a fall of nearly ten feet, that should have hurt him severely, he was not in any way injured. It was a miracle.

In Die Walküre, we had planned to have a live horse, Grane, come onstage just after Brünnhilde’s entrance in Act III. A ramp had been built, and the horse procured. After a few rehearsals we discharged the horse. First of all, it looked silly. The scene is played on a high mountain ledge. Brünnhilde comes in totally distraught. The Valkyries have described her horse as completely exhausted, because she is driving him through the air. This horse, of course, couldn’t have been quieter or calmer—as any animal has to be to appear onstage. Additionally, another event had happened. During one of the orchestra rehearsals the horse, while coming up the ramp, moved his hind legs in such a way that one of the Valkyries, Emily Pulley, was pushed off the ramp, and she fell some eight feet. Believe it or not, she wasn’t hurt either. Luck can only go so far. Goodbye horse.

One horrible event did occur. Armin Jordan, our conductor, had not been well during much of the rehearsal period. The morning after the second Walküre, he became quite ill. It was determined that the pneumonia he had had several months before had returned, and he was hospitalized in serious condition. We had a cover conductor, Franz Vote, who had prepared the whole Ring at the Metropolitan Opera for James Levine. He stepped in for the next performance, a Das Rheingold, and did all the other operas superbly. We were more than grateful to have him and more than thankful that he was so successful.

The popular and critical response to these first two operas of the cycle gave us great confidence for the next summer’s complete cycle, to which all the tickets were already sold. Now we had to do the whole show.